Maratha Administration

Central Government

- Shivaji was a not only a great warrior but a good administrator too.

- He had an advisory council to assist him in his day-to-day administration.

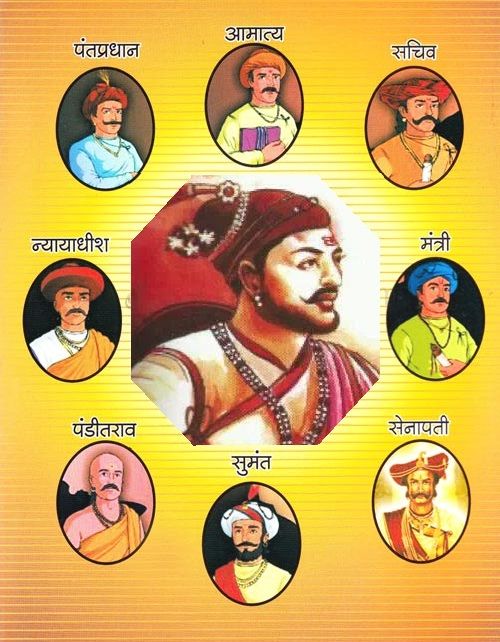

- This council of eight ministers was known as Ashta Pradhan. Its functions were advisory. The eight ministers were:

Fig : Ashta Pradhan

- The Mukhya Pradhan or Peshwa or prime minister whose duty was to look after the general welfare and interests of the State. He officiated for the king in his absence.

- The Amatya or finance minister checked and countersigned all public accounts of the kingdom.

- The Walkia-Nawis or Mantri maintained the records of the king’s activities and the proceedings in the court.

- Summant or Dabir or foreign secretary was to advise king on all matters of war and peace and to receive ambassadors and envoys from other countries.

- Sachiv or Shuru Nawis or home secretary was to look after the correspondence of the king with the power to revise the drafts. He also checked the accounts of the Parganas.

- Pandit Rao or Danadhyaksha or Sadar and Muhtasib or ecclesiastical head was in charge of religion, ceremonies and charities. He was the judge of canon law and censor of public morals.

- Nyayadhish or chief justice was responsible for civil and military justice.

- Sari Naubat or commander-in-chief was in charge of recruitment, organization and discipline of the Army.

With the exception of the Nyayadhish and Pandit Rao, all the other ministers were to command armies and lead expeditions. All royal letters, charters and treaties had to get the seal of the King and the Peshwa and the endorsement of the four ministers other than the Danadyksha, Nyayadhisha and Senapati. There were eighteen departments under the charge of the various ministers.

Provincial Government

- For the sake of administrative convenience, Shivaji divided the kingdom into four provinces, each under a viceroy.

- The provinces were divided into a number of Pranths. The practice of granting jagirs was abandoned and all officers were paid in cash.

- Even when the revenues of a particular place were assigned to any official, his only link was with the income generated from the property.

- He had no control over the people associated with it. No office was to be hereditary. The fort was the nerve-centre of the activities of the Pranth.

- The lowest unit of the government was the village in which the traditional system of administration prevailed.

Revenue System

- The revenue administration of Shivaji was humane and beneficent to the cultivators.

- The lands were carefully surveyed and assessed. The state demand was fixed at 30% of the gross produce to be payable in cash or kind.

- Later, the tax was raised to 40%. The amount of money to be paid was fixed. In times of famine, the government advanced money and grain to the cultivators which were to be paid back in instalments later.

- Liberal loans were also advanced to the peasants for purchasing cattle, seed, etc.

Chauth and Sardeshmukhi

- As the revenue collected from the state was insufficient to meet its requirements, Shivaji collected two taxes, Chauth and Sardeshmukhi, from the adjoining territories of his empire, the Mughal provinces and the territories of the Sultan of Bijapur.

- Chauth was one-fourth of the revenue of the district conquered by the Marthas.

- Sardeshmukhi was an additional 10% of the revenue which Shivaji collected by virtue of his position as Sardeshmukh.

- Sardeshmukh was the superior head of many Desais or Deshmukhs. Shivaji claimed that he was the hereditary Sardeshmukh of his country.

Military Organization

- Shivaji organized a standing army. As we have seen, he discouraged the practice of granting jagirs and making hereditary appointments.

- Quarters were provided to the soldiers. The soldiers were given regular salaries.

- The army consisted of four divisions: infantry, cavalry, an elephant corps and artillery.

- Though the soldiers were good at guerrilla methods of warfare, at a later stage they were also trained in conventional warfare.

- The infantry was divided into regiments, brigades and divisions. The smallest unit with nine soldiers was headed by a Naik (corporal).

- Each unit with 25 horsemen was placed under one havildar (equivalent to the rank of a sergeant).

- Over five havildars were placed under one jamaladar and over ten jamaladars under one hazari. Sari Naubat was the supreme commander of cavalry.

- The cavalry was divided into two classes: the bargirs (soldiers whose horses were given by the state) and the shiledars (mercenary horsemen who had to find their own horses).

- There were water-carriers and farriers too.

Justice

- The administration of justice was of a rudimentary nature. There were no regular courts and regular procedures.

- The panchayats functioned in the villages. The system of ordeals was common. Criminal cases were tried by the Patels.

- Appeals in both civil and criminal cases were heard by the Nyayadhish (chief justice) with the guidance of the smritis.

- Hazir Majlim was the final court of appeal

Maratha Administration under Peshwas (1714-1818)

- The Peshwa was one of the Ashta Pradhan of Shivaji. This office was not a hereditary one.

- As the power and prestige of the king declined, the Peshwas rose to prominence.

- The genius of Balaji Vishwanath (1713-1720) made the office of the Peshwa supreme and hereditary.

- The Peshwas virtually controlled the whole administration, usurping the powers of the king. They were also recognized as the religious head of the state.

Central Secretariat

- The centre of the Maratha administration was the Peshwa Secretariat at Poona.

- It dealt with the revenues and expenditure of all the districts, the accounts submitted by the village and district officials.

- The pay and rights of all grades of public servants and the budgets under civil, military and religious heads were also handled.

- The daily register recorded all revenues, all grants and the payments received from foreign territories.

Provinces

- Provinces under the Peshwas were of various sizes. Larger provinces were under the provincial governors called Sar-subahdars.

- The divisions in the provinces were termed Subahs and Pranths. The Mamlatdar and Kamavistar were Peshwa’s representatives in the districts.

- They were responsible for every branch of district administration.

- Deshmukhs and Deshpandes were district officers who were in charge of accounts and were to observe the activities of Mamlatdars and Kamavistars.

- It was a system of checks and balances.

- In order to prevent misappropriation of public money, the Maratha government collected a heavy sum (Rasad) from the Mamlatdars and other officials.

- It was collected on their first appointment to a district.

- In Baji Rao II’s time, these offices were auctioned off. The clerks and menials were paid for 10 or 11 months in a year.

Village Administration

- The village was the basic unit of administration and was self-supportive.

- The Patel was the chief village officer and was responsible for remitting revenue collections to the centre.

- He was not paid by the government. His post was hereditary.

- The Patel was helped by the Kulkarni or accountant and record-keeper.

- There were hereditary village servants who had to perform the communal functions.

- The carpenters, blacksmiths and other village artisans gave begar or compulsory labour.

Urban Administration

- In towns and cities the chief officer was the Kotwal.

- The maintenance of peace and order, regulation of prices, settling civil disputes and sending of monthly accounts to the governments were his main duties.

- He was the head of the city police and also functioned as the magistrate.

Sources of Revenue

- Land revenue was the main source of income. The Peshwas gave up the system of sharing the produce of the agricultural land followed under Shivaji’srule.

- The Peshwas followed the system of tax farming. Land was settled against a stipulated amount to be paid annually to the government.

- The fertility the land was assessed for fixation of taxes. Income was derived from the forests.

- Permits were given on the payment of a fee for cutting trees and using pastures.

- Revenue was derived even from the sale of grass, bamboo, fuel wood, honey and the like.

- The land revenue assessment was based on a careful survey.

- Land was divided into three classes: according to the kinds of the crops, facilities for irrigation, and productivity of the land.

- The villagers were the original settlers who acquired the forest. They could not be deprived of their lands. But only the Patel could represent their rights to the higher authorities.

Other sources of revenue were Chauth and Sardeshmukhi.

The Chauth was divided into

- 25 percent for the ruler

- 66 percent for Maratha officials and military heads for the maintenance of troops.

- 6 percent for the Pant Sachiv (Chief, a Brahman by birth)

- 3 percent for the tax collectors.

- Customs, excise duties and sale of forest produce also yielded much income. Goldsmiths were allowed to mint coins on payment of royalty to the government and getting license for the purpose.

- They had to maintain a certain standard.

- When it was found that the standard was not being met all private mints were closed in 1760 and a central mint was established.

Miscellaneous taxes were also collected. It included

- Tax on land, held by Deshmukhs and Deshpandes.

- Tax on land kept for the village Mahars.

- Tax on the lands irrigated by wells.

- House tax from all except Brahmins and village officials.

- Annual fee for the testing of weights and measures.

- Tax on the re-marriage of widows.

- Tax on sheep and buffaloes.

- Pasture fee.

- Tax on melon cultivation in river beds.

- Succession duty.

- Duty on the sale of horses, etc.

When the Maratha government was in financial difficulty, it levied on all land-holders, Kurja-Patti or Tasti-Patti, a tax equal to one year’s income of the tax-payer.

The administration of justice also earned some income. A fee of 25% was charged on money bonds. Fines were collected from persons suspected or found guilty of adultery. Brahmins were exempted from duty on things imported for their own use.

Police System

- Watchmen, generally the Mahars, were employed in every village.

- But whenever crime was on the rise, government sent forces from the irregular infantry to control crimes.

- The residents of the disturbed area had to pay an additional house tax to meet the expenditure arising out of maintaining these armed forces.

- Baji Rao II appointed additional police officers to detect and seize offenders.

- In the urban areas, magisterial and police powers were given to the Kotwal.

- Their additional duties were to monitor the prices, take a census of the inhabitants, conduct trials on civil cases, supply labour to the government and levy fees from the professional duties given to the Nagarka or police superintendent.

Judicial System

- The Judicial System was very imperfect. There was no codified law.

- There were no rules of procedure. Arbitration was given high priority.

- If it failed, then the case was transferred for decision to a panchayat appointed by the Patel in the village and by the leading merchants in towns. The panchayat was a powerful institution. Re-trial also took place. Appeals were made to the Mamlatdar.

- In criminal cases there was a hierarchy of the judicial officers. At the top was the Raja Chhatrapati and below him were the Peshwa, Sar-Subahdar, the Mamlatdar and the Patel.

- Flogging and torture were inflicted to extort confession.

Army

- The Maratha military system under the Peshwas was modelled on the Mughal military system.

- The mode of recruitment, payment of salaries, provisions for the families of the soldiers, and the importance given to the cavalry showed a strong resemblance to the Mughal military system.

- The Peshwas gave up the notable features of the military system followed under Shivaji. Shivaji had recruited soldiers locally from Maratha region.

- But the Peshwas drafted soldiers from all parts of India and from all social groups.

- The army had Arabs, Abyssinians, Rajputs, Rohillas and Sikhs. The Peshwa’s army comprised mercenaries of the feudal chieftains.

- As the fiefs of the rival chiefs were in the same area, there were lots of internal disputes. It affected the solidarity of the people of the Maratha state.

Cavalry

- The cavalry was naturally the main strength of the Maratha army.

- Every jagirdar had to bring a stipulated number of horsemen for a general muster, every year.

- The horsemen were divided into three classes based on the quality of the horses they kept.

Infantry and Artillery

- The Marathas preferred to serve in the cavalry. So men for infantry were recruited from other parts of the country.

- The Arabs, Rohillas, Sikhs and Sindhis in the Maratha infantry were paid a higher salary compared to the Maratha soldiers.

- The Maratha artillery was manned mostly by the Portuguese and Indian Christians. Later on, the English were also recruited.

Navy

- The Maratha navy was built for the purpose of guarding the Maratha ports, thereby checking piracy, and collecting customs duties from the incoming and outgoing ships.

- Balaji Vishwanath built naval bases at Konkan, Khanderi and Vijayadurg.

- Dockyard facilities were also developed.

- opularising the unique Thanjavur style of painting. Serfoji was interested in painting, gardening, coin-collecting, martial arts and patronized chariot-racing, hunting and bull-fighting.

- He created the first zoological garden in Tamilnadu in the Thanjavur palace premises.

- Serfoji II died on 7th March 1832 after almost forty years of his rule. His death was mourned throughout the kingdom and his funeral procession was attended by more than 90, 000 people.

Facts

- The Saraswati Mahal library, built by the Nayak rulers and enriched by Serfoji II contains a record of the day-to-day proceedings of the Maratha court – as Modi documents, French-Maratha correspondence of the 18th Modi was the script used to write the Marathi language. It is a treasure house of rare manuscripts and books in many languages.