Introduction

India was the first non-communist country to recognise Peples Republic of China(PRC). India supported PRC’s entry into UN. India also recognised Tibet as integral part of China. Post independence witnessed signing of PANCHSHEEL Agreement between both countries…

Why China ???

- Economic manufacturing powerhouse

- An important role to play in peace and tranquility in Asia

- Important member in multilateral diplomacy [Important for India’s entry into UNSC and NSG]

Indo China relationship can be analysed in three broad categories

–>Conflict – (Conflict resolution, Efforts towards normalisation and Confidence Building)

–>Competition – (Strategic Divergence)

–>Cooperation (Compassionate Friendship)

CONFLICT

This can be broadly classified into, tha is Direct and Indirect

Direct : Border dispute, Tibetan issue and Water war

Indirect : China – Pakistan nexus,South China Sea issue stand of India, Belt and Road Initiative, String of Pearls tactics of China, Stand of China against India in multilateral institutions such as NSG entry of India

Direct Conflict

#Border Dispute

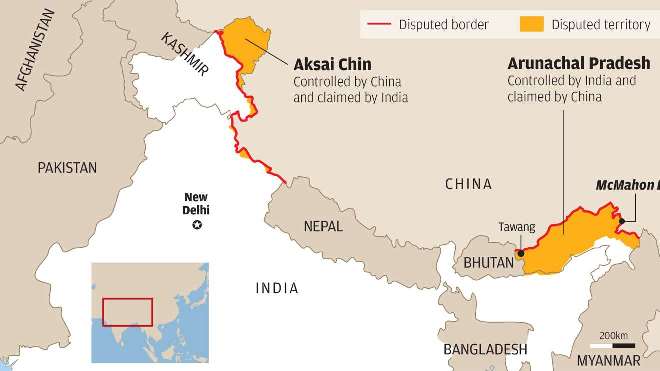

=>Conflict in Western Sector (Aksai Chin and Jammu and Kashmir)

Western Border Dispute – Johnson’s line shows Aksai Chin to be under Indian control whereas the McDonald Line places it under Chinese control. Line of Actual Control separates Indian-administered areas of J & K from Aksai Chin & is concurrent with the Chinese Aksai Chin claim line. China and India went to war in 1962 over disputed territory of Aksai Chin. India claimed this was a part of Kashmir, while China claimed it was a part of Xinjiang.

=>Conflict in Central Sector (Finger area and Sikkim)

Eastern Border Dispute: China considers the McMahon Line illegal and unacceptable claiming that Tibet had no right to sign the 1914 Convention held in Shimla which delineated the Mc Mahon line on the map – Thus claims parts of Arunachal Pradesh – India and China have held 19 rounds of Special Representative Talks on the border and there has yet to be an exchange of maps.

#Tibetan Issue

- Tibet ceased to be a political buffer when China occupied it in 1950-51

- India accepts Tibet Autonomous Region as an integral part of China and standing firmly against any anti-China activity of the Dalai Lama from Indian soil,

- India respected China’s stand on Tibet issue & never supported anti-China activities by Tibetan exiles.

- Tibet is the core issue in Beijing’s relations with countries like India, Nepal and Bhutan that traditionally did not have a common border with China. These countries became China’s neighbours after it annexed Tibet

- India’s record in terms of respecting China’s strategic sensitive is glaringly positive. India has supported the Chinese policy of “One China” principle. However, China appears to be having reservations on India’s motives with respect to the Dalai Lama. Chinese official viewed his visit to Arunachal Pradesh in November 2009, ‘further exposes the anti-china and separatist nature of the Dalai clique’ and that such visits cast a new shadow on Sino-Indian relations. This firmly points to Beijing’s approach of linking the Dalai Lama factor with the Sino-Indian border question.

- The boundary issue cannot be resolved peacefully without a solution to the status of Tibet and the return of over 94,000 registered refugeesin India. The unofficial figures are estimated to be around 150,000.

#Water War

- China’s grand plans to harness the waters of the Brahmaputra River have set off ripples of anxiety in the two lower riparian states: India and Bangladesh.

- China’s construction of dams and the proposed diversion of the Brahmaputra’s waters is not only expected to have repercussions for water flow, agriculture, ecology, and lives and livelihoods downstream; it had also become another contentious issue undermining Sino-Indian relations

- As with other rivers originating in the icy Tibetan plateau, Beijing’s plans for the Brahmaputra include two kinds of projects. The first involves the construction of hydro-electric power projects on the river and the other, more ambitious project, envisages the diversion of its waters to the arid north. In the former case, the concern would be largely about horrendous ecological impacts; in the latter, the worry would primarily be about the reduction of flows to the downstream countries. In either case, any major intervention in a river by an upstream country is always a matter of serious concern on the part of downstream countries.

- This will affect the quality of downstream water. By 2050, the annual runoff in the Brahmaputra is projected to decline by 14 per cent. This will have significant implications for food security and social stability, given the impact on climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture.

- These also raise the larger question about the cumulative impact of massive dam-building projects across the entire Himalayan region and the consequences of such intensive interventions in a region that is ecologically fragile. The dangers of water accumulation behind dams could also induce devastating artificial earthquakes.

- In a way, Indian concerns about Chinese interventions in the Brahmaputra or Yarlung Tsangpo are similar to Pakistani concerns about Indian interventions in the Indus system. The difference is that there is a treaty- the Indus Waters Treaty 1960, and an institutional arrangement, (the Permanent Indus Commission), to take care of Pakistan’s concerns vis-à-vis India, whereas India has no such treaty or institutional arrangement vis-à-vis China. We need a treaty on the Brahmaputra, but it cannot be a bilateral one between India and China; it will have to be a multilateral one covering China, India, Bhutan and Bangladesh, with a multilateral Brahmaputra Commission similar to the Mekong Commission